How to write a comic script

Table of Contents

Planning and organizationWriting out the actual scriptUse notations to make your life easierImage examplesThat's a lot of acronyms to remember...This was written by someone drawing web comics, but the concepts are the same for even traditional ones. First, some terms:

Episode - Exactly like one episode of a TV show or Webtoons; one single story or chapter.

Script - The single document describing how the episode is to be drawn (ex. dialogue, action descriptions, etc). Can contain just a part of the episode instead of the full thing.

Also, this particular workflow is centered around writing everything down. Drawing takes way too much time and I have a pretty great WPM to make the actual typing part negligible--but even if you can draw out everything at the speed of light, I do think there are some valuable suggestions here, so do try them out.

Planning and organization

I like to split my scripts into four sections:

- Meta - What lore, plot point, character development, etc. is revealed

- Summary - An overview of what happens

- To write - Anything that I want to add that I don't know how to fit in or organize coherently just yet

- Script - The contents of the script itself, eg. dialogue, poses, camera placements, etc.

Everything aside from the actual script contents is optional, but Meta should be considered in all scripts; even if your comic is a silly braincells-optional comedy or slice of life, an interesting episode (especially one that goes anywhere) will also give some sort of value to the reader. What do they learn about the world here? The plot? The characters? This is especially important in the first few episodes, when establishing the environment.

Example meta list for a first episode:

- Introduces the setting and premise

- Introduces the main character:

- Age, occupation

- Has a dog

- Implies a certain lore aspect

The Summary is useful for when you know what needs to happen in a script (or, when you're brainstorming it), but do not yet have the exact dialogue or panel-by-panel flow. Write this when you need to log down those ideas ASAP. Having a summary also allows you to read it over, see if everything fits and flows, and easily edit parts without needing to rewrite dialogue or carefully planned out scenes. The summary can also be as detailed or as rough as you want; expand on it when you have ideas.

Rough example: MC goes to the supermarket and meets the love of his life, halloumi cheese.

Detailed example: MC wakes up feeling like shit, internally groaning about the events of the last episode as he gets out of bed. The camera is placed behind him as he shuffles out the doorway and thinks about how he has to get the groceries. [...]

I always have my To Write section notes in point form. These can form into mini-summaries of their own, which is completely fine, as it will help in placing them in the right spot.

To write:

- MC seeing the cheese

- Perhaps it should fall from a high rack like falling from the heavens

- Actually no because [...]

- Perhaps it should fall from a high rack like falling from the heavens

- A passerby going "what in the actual fuck"

Writing out the actual script

I've seen a lot of people suggest that we write scripts like this:

Panel:

John picks up a random cashier by the collar and yells.

John: WHERE IS THE CHEESE?!

The cashier trembles with his head half turned away.

Cashier: S-sir, this is a flower shop...

Panel:

[... (next panel contents)]

But there are several things wrong with this approach:

- You are writing a comic, everything is a panel. There is no point in specifying it.

- You have to write 'John' twice--once for his actions, and once for his dialogue--and when there are other characters in the panel, you're probably rewriting their names too. Even using pronouns inferred to by the context is redundant.

- You're writing the character's full name. What if this guy has a name that's 20 letters long? A name with an accented mark that's annoying to type? What if you haven't come up a name for him yet?

- There is no direction. Maybe you have the picture clear in your mind, but whether you'll remember it by the time you draw is something different; where is the camera placed in this scene, at this particular moment in time? Does the yelling speech bubble look like a white explosion, or is it inverted with black background and a scary font? How big is this panel? Are there explosive action lines? Which configurations give a better flow and impact?

As you can see, there are a shitload of things to consider when drawing a single panel. A good portion of the time this does come naturally when you're in the flow, but if you're writing it down, then you'll want to note down everything else so that you won't have to figure it all out again when you actually draw it.

Use notations to make your life easier

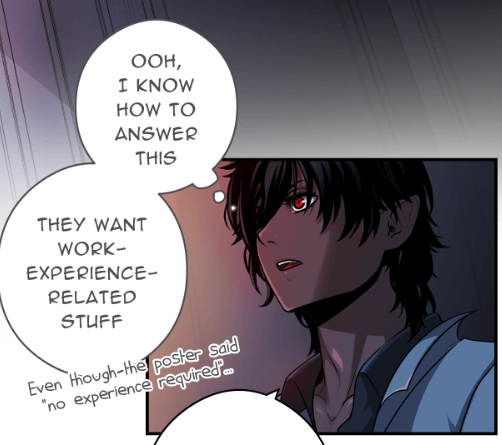

Here is the same script as above, but written using notations (the acronyms used will be explained later):

- J: |LP| *picks up a random cashier (C) by the collar, yells into his face, camera framing them both close torso-up* |EAL, ESB| WHERE IS THE CHEESE?

- C: *trembles, head half turned away* |WB| S-sir, this is a flower shop... // |ST| Tremble

This immediately solves many redundancy problems, and gives way to a descriptive panel without needing to make prose:

- Characters are referred to with one letter (maximum 2). Not only is this a lot faster to type, but it also doesn't bind anyone to a name; it could be a role, like MC for Main Character or C for cashier in this case, allowing one-off characters to be referred to easily. (Imagine writing a scene where your character consults a doctor and having to write out "Doctor" 50 times)

- Character actions are written write beside the character's identifier, so there is no need to re-identify them separately. You can also skip a lot of text by removing the need for full sentence structure.

- Everything under a single panel is indented. So you don't need any markers or double linebreaks to define a separate panel; as long as they're not indented, they are a single panel.

- Camera placement is addressed, smoothly flowing and relating from the character's action. You can go further and specify the mood of the panel for better lighting in the drawing stage if needed.

- The panel size, bubble appearances, and even more is addressed with the use of notations. Below is a list of everything that was used here:

- LP = Large panel

- EAL = Explosive action lines

- ESB = Explosive speech bubble

- WB = Wobbly bubble

- ST = Small floating text

- // (double slash) = Space this text away from the previous line (further explanation and image example below)

All notations/acronyms are based on things that I use a lot. The list is ever-expanding; if I find myself writing out a certain bubble style, text style, or any other direction a lot, I will add it to the list.

Image examples

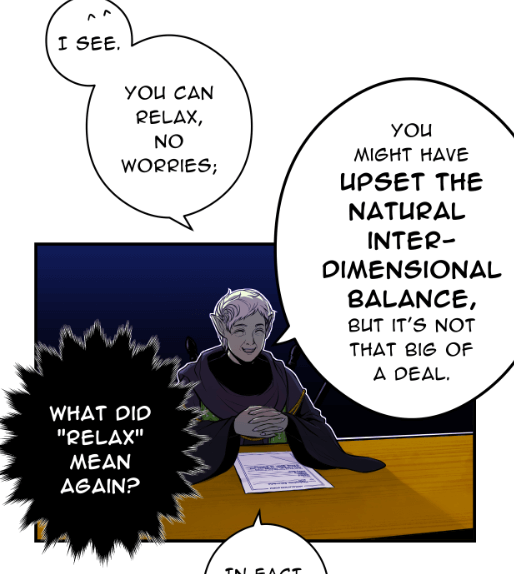

Bubble spacing is something that changes the mood of the dialogue quite a bit. Think of it as the character taking a short pause in-between their sentences; can be used for dramatic effect, and also just readability.

Because this system is anti-linebreaks however (think of how messy it would get!), all bubble spacing is denoted by either a single slash or a double slash. Single slash is good for short pauses, or just to break up long text, while double slash means "(pull this bubble all the way to the other corner of the panel, or at least leave a larger gap)". The panel below uses both of these:

BT (bold text),

SBO (speech bubble only), and

N ('normal' text to know when to reset previous formatting)

- E: *^_^* I see. / You can relax, no worries; // you might have |BT| upset the natural interdimensional balance, |N| but it's not that big of a deal.

- M: |SBO, ETB| What did "Relax" mean again?

- E: In fact [...]

That's a lot of acronyms to remember...

Except it's actually not!

Think of all the words there are in whatever language you're most fluent in. Do you have trouble remembering those words? Do you have to refer to the dictionary every time you want to say something?

As long as you're using these acronyms on a daily basis (or however often you write comics), and they're notations that makes sense to you, they will stick. I have never had trouble remembering any of the ones I showed in this post, and there is a lot, lot more of them I use frequently.

That said, yes, there are times where I might have used something in a particular script a lot but not outside of it, or in one project of a certain genre but not the other (you're not going to see TADA in a serious comic). But there's no problem with that. Why? Because I can just write them down!

This is common sense, but every time you come up with a new notation, just write it down on some sort of reference document that you can easily find and search through; the same as creating character sheets or lore. Exactly how you structure this document (and the rest of your project) is up to what works best for you, but for anyone interested, I'll have a post on project management coming up soon. (Subscribe in the footer down below to be notified when it gets posted!)

Spirall

Spirall